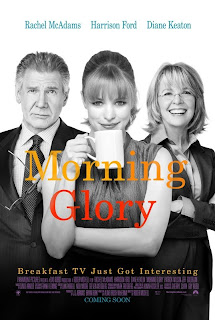

Daybreak, gentlemen! The daily five-ay-em pitch-meeting of the self. Rachel McAdams plays a 28-year-old aspiring morning-show producer hired to revitalize the sinking program on which Annie Hall daily demeans herself. The clincher, at the job interview: “I know a shitload more about news than someone whose daddy paid them to smoke bongs and talk semiotics at Harvard!” Come on, everyone knows semioticians prefer blunts. Is she just trying to get us not to read the shot that has her eating her lunch-salad from its little plastic clamshell while sitting next to the Gertrude Stein statue in Bryant Park? I mean, I only went to state school but the significance seems clear: language nibbles, rabbit-like, or laps, lover-like, at the event, it is not what is new but what is news, the for-some-reason plural (=hyperactive) nature of our encounter with the present, by which I mean that each morning we apply to our only face, or in McAdams’s case her really cute legs, the cold razor of the now, and that razor has not one, not two, not three, but four merciless blades.

And whose face has been there, who growls when aroused? She forces Harrison Ford (Extraordinary Measures) to co-anchor the show, and in return he tells her she has “father issues” and “repellent moxie,” and makes an uncalled-for crack about her bangs. Does he suspect she’s a replicant (she is, after all, a Plastic)? You’re watching t.v. and a wasp lands on your arm. He’s mad he’s not getting to do the serious television news. Huh?

You see what I’m getting at? Patrick Wilson tells her to meet him after work for drinks at “Schiller’s on Madison Avenue.” And then a little later we see the exterior shot of Schiller’s—the lemondrop-yellow “LIQUOR BAR” sign—which is of course on the Lower East Side. And why try to get away with that? Or rather, since they know they won’t, what’s the ploy? I love the mother, who at the beginning of the film tells McAdams that her career dream, by this point in her life (28!), is getting “embarrassing”—“I just want you to stop before we get to heartbreaking.” Raise your hand if you’ve ever done one of those Working Girl commutes, Carly Simon surging in your mind. Raise your hand if you’ve ever done one of those last-reel runs across New York towards the thing you really want. Or were you just running to catch a film? Actual conversation’s tail-end, overheard on the ticket line: Young woman: “So why are you doing it?” Young man: “Because you only live once.” So what if you run all the way over to Madison Avenue, only to find that Schiller’s isn’t there? Oh God, what the hell am I doing with my life?